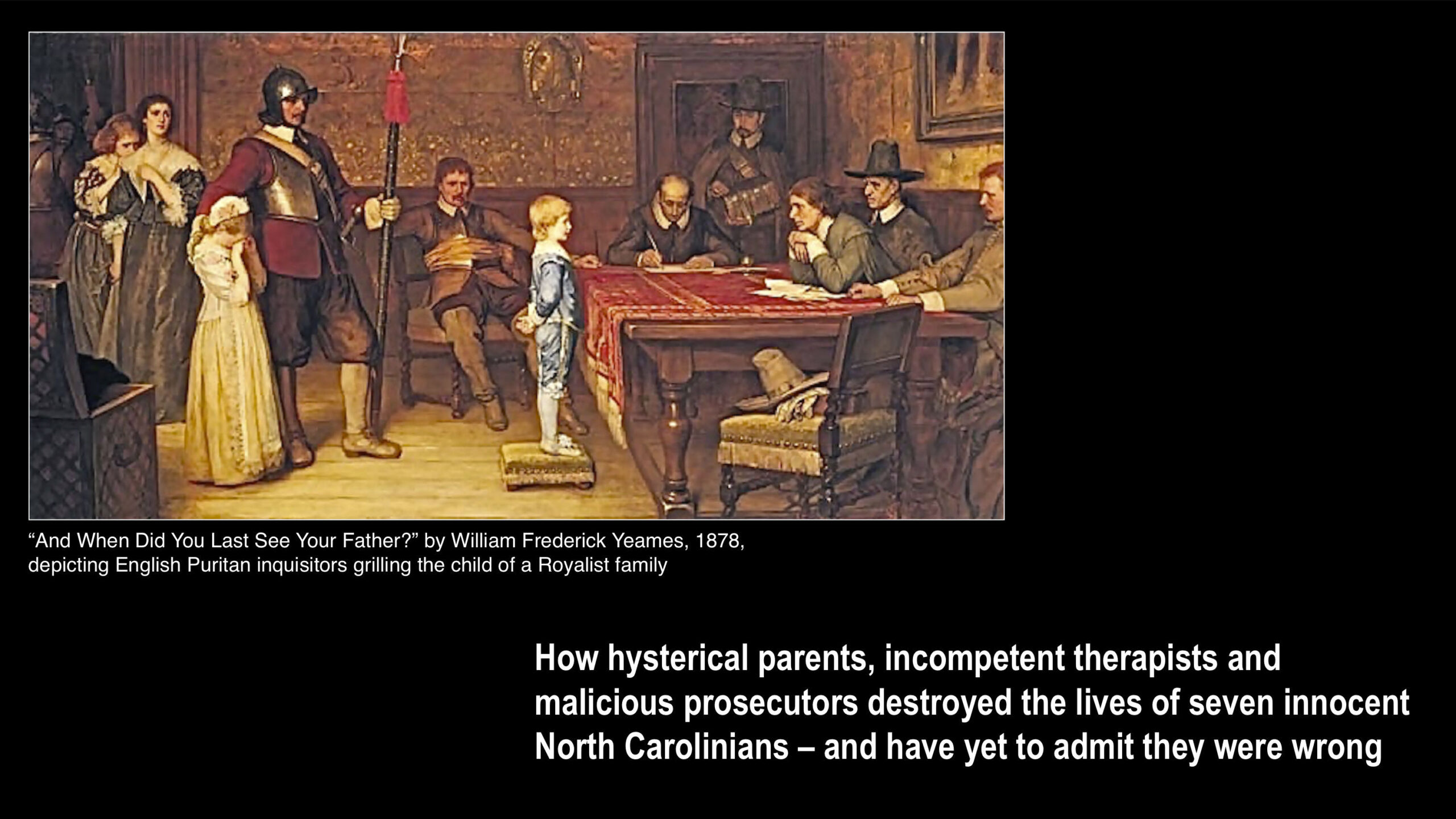

Rascals case in brief

In the beginning, in 1989, more than 90 children at the Little Rascals Day Care Center in Edenton, North Carolina, accused a total of 20 adults with 429 instances of sexual abuse over a three-year period. It may have all begun with one parent’s complaint about punishment given her child.

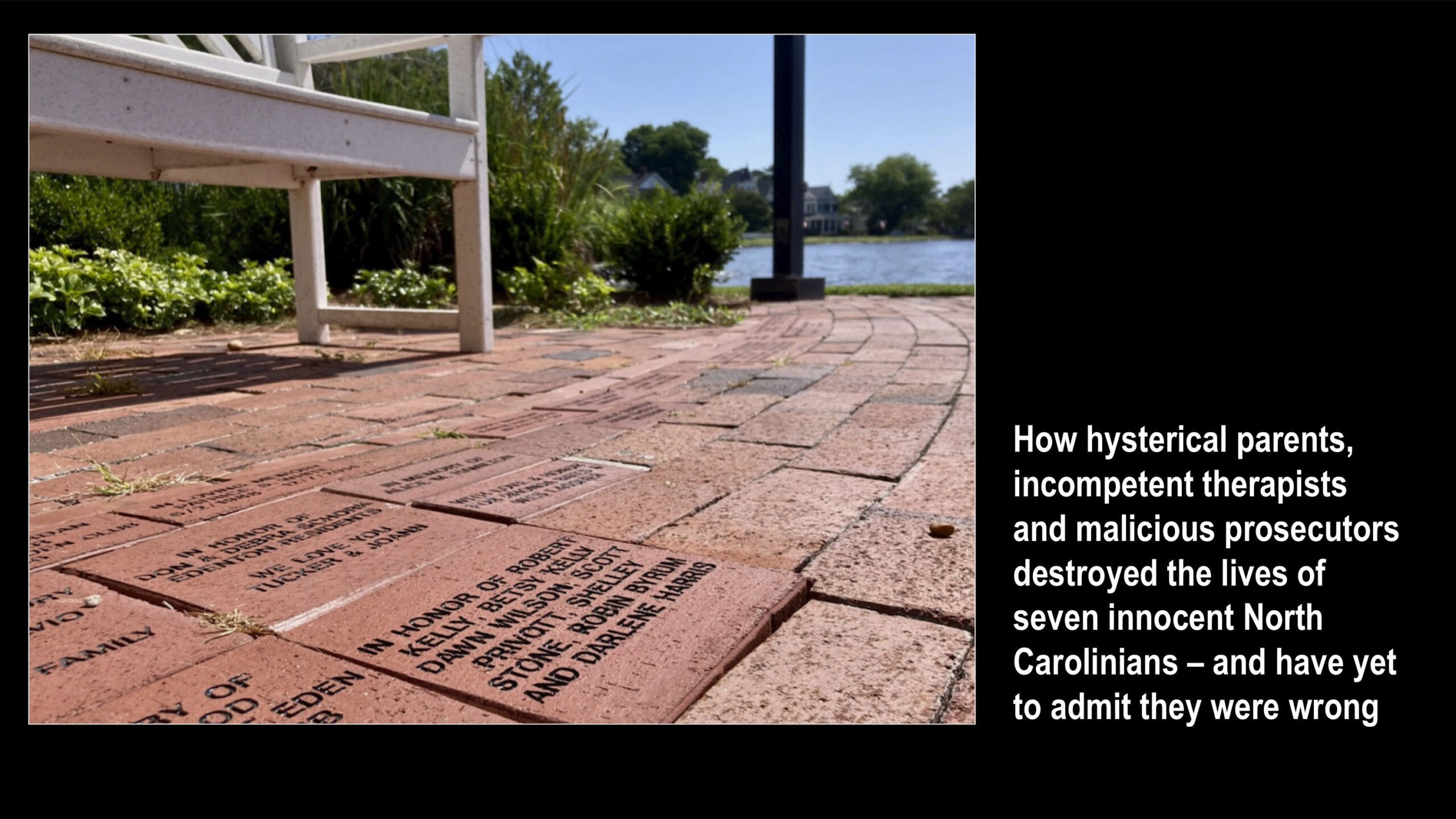

Among the alleged perpetrators: the sheriff and mayor. But prosecutors would charge only Robin Byrum, Darlene Harris, Elizabeth “Betsy” Kelly, Robert “Bob” Kelly, Willard Scott Privott, Shelley Stone and Dawn Wilson – the Edenton 7.

Along with sodomy and beatings, allegations included a baby killed with a handgun, a child being hung upside down from a tree and being set on fire and countless other fantastic incidents involving spaceships, hot air balloons, pirate ships and trained sharks.

By the time prosecutors dropped the last charges in 1997, Little Rascals had become North Carolina’s longest and most costly criminal trial. Prosecutors kept defendants jailed in hopes at least one would turn against their supposed co-conspirators. Remarkably, none did. Another shameful record: Five defendants had to wait longer to face their accusers in court than anyone else in North Carolina history.

Between 1991 and 1997, Ofra Bikel produced three extraordinary episodes on the Little Rascals case for the PBS series “Frontline.” Although “Innocence Lost” did not deter prosecutors, it exposed their tactics and fostered nationwide skepticism and dismay.

With each passing year, the absurdity of the Little Rascals charges has become more obvious. But no admission of error has ever come from prosecutors, police, interviewers or parents. This site is devoted to the issues raised by this case.

On Facebook

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

‘Will Edenton be able to heal from this?’

Aug. 7, 2013

Aug. 7, 2013

“After (the first episode of “Innocence Lost” aired in 1991), letters and phone calls poured into the mayor’s office.

“ ‘Dear Mayor: Thank God I don’t live in Edenton. It’s full of witches…..’

“ ‘Dear Mayor: I suppose since lynching Negroes is verboten, the next best thing is for Southerners to cannibalize each other….’

“John Dowd, Edenton’s mayor at the time, is trying to correct some of the damage done to the town’s reputation….

“Many reporters have wanted to know: ‘Will Edenton be able to heal from this?’ The question is a little too touchy-feely for some residents, too intimate and much too insincere. Dowd replies, ‘Hell, we’ve recovered from the Civil War, from World War II.’ Then, dryly: ‘Yeah, I think we’ll recover from this.’ ”

– From “Little Town of Horrors” by Kathy Dobie in McCall’s (June 1992)

The Civil War, World War II and the Little Rascals Day Care case? The mayor’s resolve was apparent, if not his logic – but that was true for the whole case, wasn’t it?

Building a better mousetrap? Not exactly….

Aug. 24, 2014

Aug. 24, 2014

“The following dialogue is from Daniel Goleman’s article ‘Studies Reflect Suggestibility of Very Young as Witnesses,’ in the New York Times (June 11, 1993). It is an excerpt from 11 interviews of a four-year-old boy, who each week was told falsely: ‘You went to the hospital because your finger got caught in a mousetrap. Did this ever happen to you?’

“First Interview: ‘No. I’ve never been to the hospital.’

“Second Interview: ‘Yes. I cried.’

“Third Interview: ‘Yes. My mom went to the hospital with me.’

“Fourth Interview: ‘Yes. I remember. It felt like a cut.’

“Fifth Interview: ‘Yes.’ (Pointing to index finger….)

“Eleventh Interview: ‘Uh huh. My daddy, mommy, and my brother (took me to the hospital) in our van…. The hospital gave me . . . a little bandage, and it was right here’ (pointing to index finger).

“The interviewer then asked: ‘How did it happen?’

“ ‘I was looking and then I didn’t see what I was doing and it (finger) got in there somehow…. The mousetrap was in our house because there’s a mouse in our house…. The mousetrap is down in the basement next to the firewood…. I was playing a game called “Operation” and then I went downstairs and said to Dad, “I want to eat lunch” and then it got stuck in the mousetrap…. My daddy was down in the basement collecting firewood…. (My brother) pushed me into the mousetrap…. It happened yesterday. The mouse was in my house yesterday. I caught my finger in it yesterday. I went to the hospital yesterday.’ “

– From “Case Study of Implanted Memory” by Martin Gardner in Skeptical Inquirer (Fall 1994)

Does this experiment’s series of 11 interviews strike you as extreme? For at least one of the Little Rascals children, Judith Abbott, lead therapist for the prosecution, conducted biweekly sessions for six months!

Journalists, too, suffer ‘incurable blind spots’

Jan. 4, 2012

“A few years back, I met a fellow investigative journalist in North Carolina….The subject came around to the Little Rascals case. He assured me the day care workers were guilty….

“A few years back, I met a fellow investigative journalist in North Carolina….The subject came around to the Little Rascals case. He assured me the day care workers were guilty….

“I told him about how the McMartin case in California had been the first nationally publicized case to use interviews that practically bullied children into reporting mythical, often totally implausible abuse. Little Rascals was a textbook case of the same kind of tactics, and Ofra Bikel’s three fine documentaries left no doubt about this terrible miscarriage of justice.

“Yet my friend refused to listen to any other evidence or point of view. It transpired that his wife had recovered ‘memories’ of sexual abuse – another subject on which he would hear no other evidence….

“I tell you this just to let you know I am familiar with cases in which otherwise objective journalists develop seemingly incurable blind spots.”

– From a 1997 letter to Columbia Journalism Review by Mark Pendergrast, author of “Victims of Memory,” challenging criticism of the False Memory Syndrome Foundation

Blogger writes about Lew Powell’s writing about Little Rascals case

Aug. 9, 2012

Text of Bill Lucey’s blog item about Lew Powell’s writing on the Little Rascals case.

Retired Charlotte Observer Columnist Lew Powell Pursuing

State’s Admission of Guilt in Witch Hunt of Wrongly Accused

After being laid-off from the Charlotte Observer after 34 years in 2009, Lew Powell took the news not as the end, but as a new beginning to explore with great vigor a single issue (a colossal miscarriage of justice in his view) that has consumed him since the 1990’s. It has also freed him to spend more time on his real passion: the unique history of the Tar Heel State.

Since leaving the Observer, Powell has contributed more than 700 posts to the North Carolina Miscellany blog, a blog produced, edited, and maintained by the North Carolina Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, which documents the history, literature, and culture of North Carolina. It is reportedly the largest state collection of its kind in the country.

Powell is exceptionally adept at unraveling the origins of symbols and traditions in North Carolina. His 34 years of newspaper experience at the Observer gives the North Carolina Miscellany a reliable voice with over three decades of institutional experience to draw from, as well as become the beneficiaries of a treasure chest of memorabilia. Powell has donated 2,698 North Carolina-related pin-back buttons, badges, ribbons, cloth swatches, promotional cards and stickers, which he collected over the years.

His unique grasp of North Carolina has resulted in books that can’t help but benefit residents of the Tar Heel State starved to discover a treasury of unique and largely unknown facts. Powell is author of the “Ultimate North Carolina Quiz Book’’, “On This Day in North Carolina’’ and “Lew Powell’s Carolina Follies’’ , a collection of 200 of his satirical year-in-review pages from The Charlotte Observer.

Despite his strong interest in North Carolina history, beginning about a year ago, Powell spends the bulk of his time researching and collecting facts on the Little Rascals Day Care Center, a facility located in Edenton, North Carolina, which had been owned by Betsy and Bob Kelly.

At the Center, Kelly was charged along with six others in 1989 with molesting 29 children attending the Little Rascals day care center. He was convicted in 1992 and sentenced to 12 life terms. Kathryn Dawn Wilson, a cook at the Center was found guilty in 1993. Both convictions, however, were overturned when the North Carolina Court of Appeals stated that there were “legal errors’’ by the prosecution. On May 23, 1997, all charges against were dismissed. Elizabeth Kelly and another defendant reached plea bargains in which they agreed to jail time served, according to reporting from The Associated Press.

The case caught the eye of Powell ever since the airing of the PBS special in which “Frontline“ producer Ofra Bikel profiled Edenton, N.C., a town in Chowan County, North Carolina (population 4,966) located in the state’s Inner Banks region. The 1991 report chronicled the way in which this small sleepy town was torn by allegations of child abuse at the Little Rascals Day-Care Center. In 1993, Frontline’s follow-up investigation raised serious questions about the evidence and the fairness of the trials. Between 1991 and 1997, “Frontline’’ devoted eight hours to the plight of the Edenton Seven, leaving many, perhaps millions, shocked at the way North Carolina so recklessly prosecuted the case.

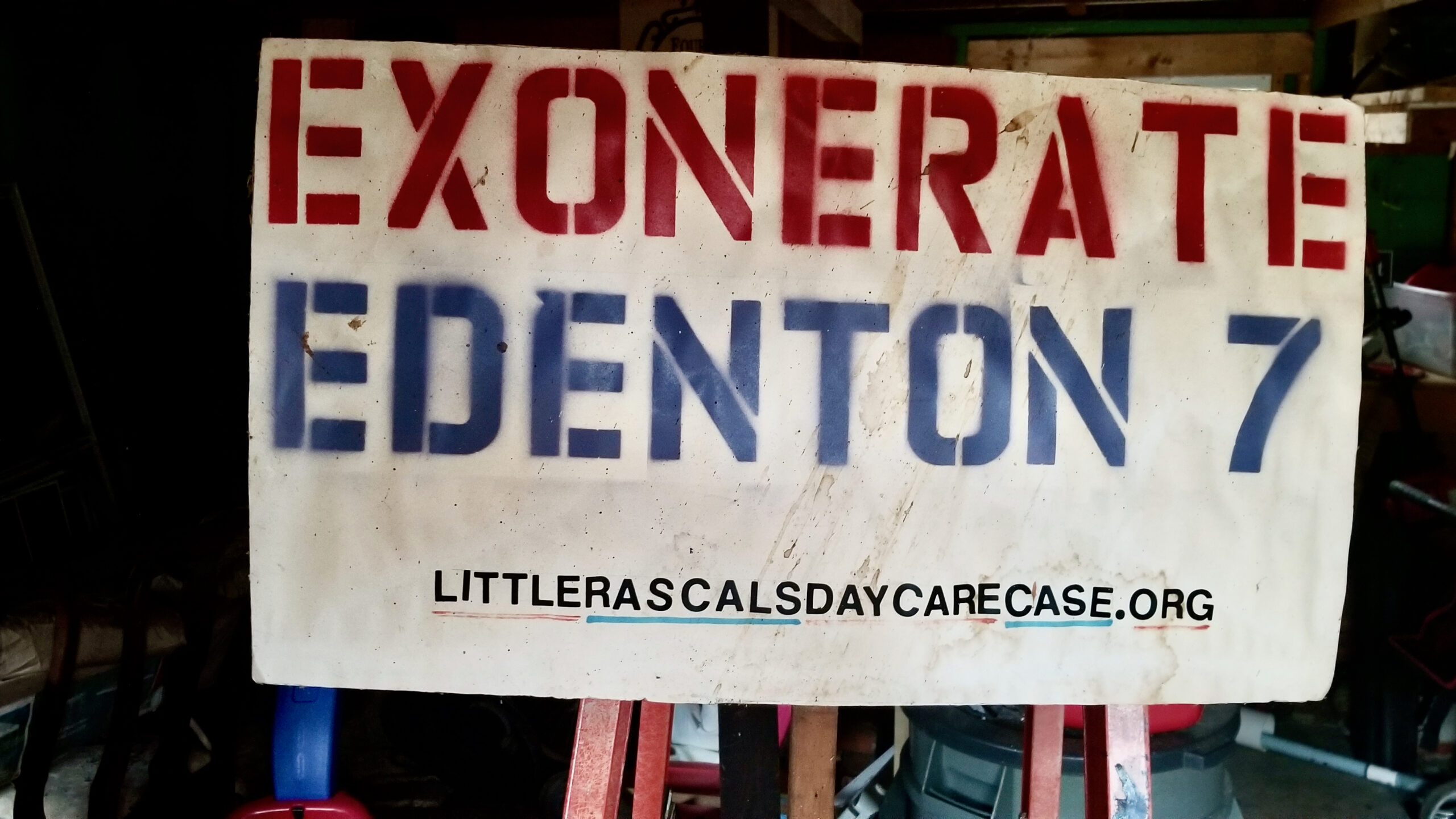

Powell was so outraged by the case in which he insists innocent people were wrongly accused in what was nothing more than a witch hunt, has since started a blog, littlerascalsdaycarecase.org .

Powell said since October, he posts about three times a week, updating it with more information and relevant material. “Retirement has allowed me to reexamine details of the case,’’ Powell said, “to put it in the context of a decade of day-care ritual-abuse panic and to question those who invented and prosecuted the completely groundless charges.

“Most interesting to me has been the refusal of all the theoreticians and therapists behind the “moral panic” to acknowledge that “science and the law have completely discredited the interviewing techniques that led to Little Rascals,’’ Powell explained to me.

In this highly controversial case, which drew the attention of the national media, children testified they were forced to have sex with adults and each other at the day care center and other places. Tales of spaceships and trained sharks were also part of their testimony. The defense long argued the children were “coached’’ into telling manufactured stories that were more in tune with the parents “fears’’ than the reality of what actually happened.

Though the accused had their cases overturned, Powell is mainly irked that the state continues to claim they were guilty and refuses to acknowledge mistakes were made in their unsubstantiated prosecutorial methods.

One of Powell’s goals, however quixotic it may be, is to secure a statement of innocence from the State of North Carolina.

In a letter he wrote to Roy Cooper, North Carolina attorney general, Powell likens the case to the 2006 Duke Lacrosse scandal in which false charges of rape by three members of the team were made and led to the disbarment of lead prosecutor Mike Nifong. In his letter to the North Carolina Attorney General, Powell mentions the state granted the defendants a “statement of innocence.’’ Powell requested the state take similar action with those wrongly accused in the Little Rascal case.

In his letter, Powell writes: “For more than a decade, beginning in the 1980s, day care centers across the United States were victimized by a wave of wholly unsubstantiated charges of ‘ritual sexual abuse.’ The testimony of child-witnesses, corrupted by misguided therapists, resulted in dozens of convictions and incarcerations. The defendants were innocent victims of a ‘moral panic’ that bore striking similarities to the Salem witch hunts 300 years earlier.’’

Powell argues the case not only shattered innocent lives, “but also left a deep and ugly stain on the reputation of the State of North Carolina.’’

With Massachusetts Governor Jane Swift having signed a resolution in 2001, proclaiming the innocence of the victims of the Salem Witch Trials, why not, Powell asks, shouldn’t the same resolution be extended to the Edenton Seven?

“Exoneration for the Edenton Seven seems as distant a prospect as ever,’’ Powell tells me. Still, despite having the former district attorney slamming the phone in his ear, when he asked him if still believed they were guilty, Powell said he continues to pursue more leads, and still has stacked in his garage 11 unopened boxes of trial transcripts.

Before landing at the Observer in 1974 as a feature writer, Powell was a reporter and editor at the Jacksonville (Fla.) Journal, and the Delta Democrat-Times. He has additionally contributed articles to the Nation, Columbia Journalism Review, and The New York Times op-ed page.

It was at the Observer where Powell met his wife, Dannye Romine.

Born in the rural town of Helena, Arkansas, Powell grew up in a farming family in Mississippi, where he graduated from the University of Mississippi with a degree in accounting.

When he retired from the Observer in 2009, Powell was the paper’s Forum editor.

– Bill Lucey

[email protected]

August 9, 2012

0 CommentsComment on Facebook